We can never forget Korey Stringer, who collapsed on a Minnesota practice field on a sweltering July afternoon in 2001, died of heat stroke early the next morning and reminded the world that football players are not indestructible.

Stringer died 14 years ago, a victim of oppressive heat and national misunderstanding of—and indifference about—a dangerous-but-preventable ailment that still claims the lives of too many young athletes each year.

Stringer’s death opened eyes and minds about the dangers of dehydration and heat stroke. It prompted immediate changes in how the NFL and NCAA treat their athletes during steamy summer practices, changes that trickled down to prep and youth levels. It even changed the tone of the national football conversation, creating an awareness of the perils of playing football that has carried over to other health and safety issues.

Stringer’s death saved countless lives. But there are many more lives to be saved. We can never forget Stringer: his career, his sacrifice, his legacy.

The Beauty of Everyday Things

Rookie Korey Stringer was ready for anything the NFL could throw at him except Reggie White.

Stringer was not yet 21 years old when the Vikings selected him in the first round of the 1995 draft. He was one of the youngest players ever drafted, and he became a starter at right tackle early in the 1995 season.

He fared well in his first starts, but White already had one foot in the Hall of Fame.

The press built up the “Reggie versus Rookie” narrative during the run-up to that October game. The Minneapolis Star-Tribune profiled Stringer’s preparation for White; the rookie pounded his feet while jogging on a treadmill at 6:45 a.m. to shed weight and thumbed through a phone bill listing $579 worth of homesick calls for the month.

“Everyone acts like it’s going to be my funeral this week,” Stringer told Selena Roberts.

Stringer started the game but had to exit with what was called a stomach injury in the newspapers.

The details of the injury? “He had food poisoning,” fellow lineman David Dixon recalled in a recent interview with Bleacher Report.

A backup replaced Stringer but was hopeless against White.

“I said, ‘Hell, let me go out there,'” said Dixon, a guard by trade. “So I played right tackle, and Reggie White just gave me the infamous ‘hump’ move. He took me out of the way, hit Warren Moon, made him fumble the ball. They scooped it up for a touchdown.”

The Sean Jones fumble recovery gave the Packers a 35-14 lead, making the game a rout.

“[Coach] Denny [Green] said ‘Get your butt back in at right guard,'” Dixon remembered.

Stringer and Dixon recovered from the experience. They became training-camp and road-trip roommates.

“We were just two young players trying to find some cohesiveness,” Dixon recalled.

Back in 1995, the left side of the Vikings line boasted Pro Bowlers Todd Steussie and Randall McDaniel. Center Jeff Christy was also a three-time Pro Bowler. Over the years, Dixon and Stringer grew into their roles on the right side. By 1998, the Vikings were a 15-1 team, and Randall Cunningham suffered just 20 sacks behind one of the NFL’s most stable lines.

By 2000, Christy and Randall were gone, Stringer and Dixon were veterans and the Vikings still had one of the league’s best offenses, now with second-year quarterback Daunte Culpepper pulling the trigger and hurling bombs at Cris Carter and Randy Moss.

Matt Birk, Christy’s replacement at center, got some predictable Welcome to the NFL treatment from Stringer when he arrived as a late-round rookie.

“He was tough at first, on purpose,” Birk recalled. “It wasn’t hazing, but he was like, ‘Hey rookie, do this, do that, you gotta earn your way around here.’

“But quickly thereafter, he would sit there and answer questions about life, relationships. He was always very open, very honest and very approachable, even though he had a rough exterior.”

Stringer had what Dixon called a “quiet” sense of humor. He performed impressions of Vikings staffers, though he never took the impersonations too far. “He found the humor and beauty in everyday things,” Birk said. “Little things that you’d never even notice, he’d point out and thought they were so funny or so joyous.”

Stringer and Birk made the Pro Bowl for the Vikings in 2000, as did most of the skill-position stars of that high-powered offense. But the Giants dismantled the Vikings 41-0 in the NFC championship game, with Stringer having a rough game against Michael Strahan. The Vikings offense went to Honolulu, then arrived in Mankato training camp the next summer eager to prove they could do more than produce fantasy statistics.

Then, on a sweltering morning in July, Stringer collapsed and everyone’s priorities changed.

Disbelief

“It had been a scorcher of a morning,” wrote Brett Knapp in the Rapid City Journal on the morning Stringer died. Humidity was high, temperatures were in the low 90s.

“It was hot,” Birk remembered, but no more so than any other day in training camp. “Hot days in Mankato, Minnesota, in summer are nothing new.”

It was a Tuesday. Practices began in earnest that Monday. Even players who participated in the team’s offseason workout program were just trying to cope, and Stringer had not been a full participant.

“I was struggling too,” said Dixon. “It wasn’t like I was 100 percent either.”

Coaches ordered the offensive line to participate in extra work after a practice session that lasted over two hours. Dixon relayed the bad news to Stringer on the field. Both would have to “suck it up” and practice a little more.

Birk was hot and tired as well.

“Korey was just like everybody else,” he said. “And then, one time, he slowly went down to the ground. He went down to the knee and then rolled over.”

Birk asked Stringer if he was OK. Stringer asked for a trainer.

“He was very calm,” Birk recalled.

Knapp reported that he left an interview session to watch the extra lineman drills. The reporter was just leaving for the air-conditioned media center when Stringer nearly knocked him over in his rush to the trainer’s room.

“In truth, he wasn’t so much walking as he was lurching and stumbling, his eyes a bit glassed over and his face contorted with pain,” Knapp reported. “By the time he reached the door and walked through, Stringer looked barely able to keep moving under his own power.

“They would be some of the last steps he ever took.”

Birk thought little of Stringer’s status that afternoon. There was nothing that unusual about a player needing an IV or even brief hospitalization in the sweltering early days of camp. Teammates often showed up for dinner after treatment.

Dixon had not even noticed that Stringer, his roommate and the player who lined up beside him for years, had left the field. When Dixon saw that several teammates were missing from afternoon meetings, he realized the severity of the situation and headed to the hospital.

Teammates were not allowed to see Stringer. There were whispers and rumors. Dixon returned to training camp.

Stringer died at 1:35 a.m. on the morning of Aug. 1. His body had reached a core temperature of 108 degrees. He had lost consciousness sometime after asking Birk for help and tumbling past the freelance reporter who ultimately broke the story of his death.

“It was just disbelief,” Birk said. “Disbelief that that could happen.”

Within hours, heat stroke and dehydration—a pair of dull medical subjects few people wrote or talked about—became the only topics anyone was talking about.

Preventable Killer

Heat stroke occurs when a person’s core body temperature exceeds 105 degrees Fahrenheit. Nausea and disorientation are the most common early symptoms. The longer the core body temperature stays high, the greater the risk of serious, permanent consequences. The high heat makes organs swell and shut down and wreaks havoc on the nervous system. Without cooling and rehydration, a heat stroke victim is likely to lapse into a coma, then die.

Doctor Douglas Casa suffered his first heat stroke as a teenager, running a 10K race at the Empire State Games in the 1980s. He stumbled late in the race from dizziness, rose to his feet, then fell again. After receiving successful treatment, he devoted his studies to exertional heat illnesses. Casa is now the chief operating officer of the Korey Stringer Institute, as well as a professor of kinesiology at the University of Connecticut.

Casa’s goal is to get youth, prep, college and pro coaches, trainers, athletic associations and school boards to adopt some simple protocols and standards that can all but eradicate the risks of heat stroke deaths.

“Obviously, having a home that’s named after Korey Stringer’s legacy gives us more reach,” he said.

Treatment of heat stroke is somewhat counterintuitive. It’s one of the few illness for which rushing to the hospital is a bad idea.

“You actually want to treat it on site,” Casa said. “We call it cool first, transport second. If you have 30 minutes to work with, you can’t wait 10 minutes for an ambulance.”

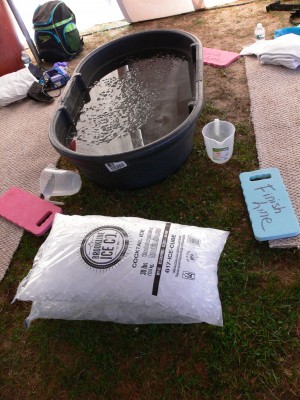

Submerging a heat stroke victim in a cooling tub can immediately start lowering the core body temperature. Casa’s research reports a 100 percent survival rate in cases where the core body temperature was cooled to below 105.5 degrees in the first half hour.

The best way to prevent heat stroke deaths is to prevent heat stroke. Casa and the Korey Stringer Institute list what Casa calls “four big-ticket items” for heat stroke prevention:

Hydration: Drinking plenty of the right kinds of fluids before, during and after exertion is an obvious and important way to prevent heat stroke, but it is not a cure-all. “That’s only one piece of the puzzle, and it distracts people. They think that it’s the only element to prevent heat stroke.”

Heat Acclimatization: There’s more to getting used to the heat than mentally preparing to be all sweaty. “Your body actually goes through some amazing physiological changes in that first week to protect you,” Casa said.

In football terms, heat acclimatization means eliminating two-a-days early in the practice season and generally ramping up exertion levels in high-risk conditions to ensure that, for example, a high school freshman doesn’t go straight from a July of swimming and air conditioning to a week of six-hour, 95-degree practice in August. Casa reported that 90 percent of all heat stroke deaths, like Stringer’s, occur during the first three days of activity.

Work-to-Rest Ratios: “This is not rocket science,” Casa said. “If it is brutally hot out, we are going to have more rest breaks.”

Body Cooling Throughout the Session: Drink breaks, ice packs, shaded areas, some cold wet towels for the player’s neck and back.

The Korey Stringer Institute’s unofficial fifth “big-ticket item” is education. The NFL changed its heat-illness priorities soon after Stringer’s death. The NCAA adopted a sweeping reform in 2003. The mistakes that led to Stringer’s death—immediate high-intensity exertion at the start of camp, hydration on a have a drink when thirstybasis, transportation before cooling—were addressed and reduced or eliminated.

NFL and college players can count on the presence of immersion tubs close to the practice field and trainers who recognize symptoms and best-treatment practices and practice routines that reflect modern heat stroke research.

Unfortunately, high school players may attend a school that does not even have athletic trainers, with a school board that never approved an emergency heat stroke protocol, in one of the 36 states that do not meet the KSI’s minimum safety standards, with a coach who thinks six-hour introductory practices toughen the kids up.

The NFL hosted a heat stroke seminar for the leaders of all 50 state high school athletic associations early this year.

“That was probably the most useful two days of my whole career,” Casa said.

State officials compared notes and learned what their neighbors were doing. The NFL’s involvement gave the seminar clout (the NCAA will host another one next year), and Stringer’s legacy carried influence among the attendees.

“Most of the people were between 35 and 55 years old,” Casa said. “They all, in the front of their minds, remember Korey Stringer.”

The Worst Wake-Up Call

David Dixon didn’t feel so good. It was Vikings training camp in 2002 or 2003, a year or two after Stringer’s death, and the heat was taking its toll on the veteran lineman. He asked for some Gatorade. After a drink, he still felt sick.

“They took me out,” Dixon said. “They put me in the medical tent. They put IVs in me. They put some ice bags underneath my armpits and in between my legs.”

Dixon wasn’t scared. He understood the symptoms of dehydration and knew that he and the training staff got a jump on the condition. He was more concerned about the next day’s weigh-ins.

“I told them, ‘Get this damn IV out of me! I’ll be five pounds over my weight from all this fluid going into my system!'”

Dixon was excused from weigh-ins so he could finish his treatment.

Needless to say, times changed after Stringer’s death, not just in Minnesota but at football camps at all levels around the country. Unless he was an All-Pro, no NFL player would have risked asking for a Gatorade break and some ice packs for a little thing like dizziness a decade earlier. Dixon chuckled at the probable response: “Here’s your pink paper. You can go home.”

Birk remembers the changes occurring almost overnight. “After that, they pulled the soda machines out of the dining hall,” he said. “It was almost instant change all over the league.”

Teams began to focus on hydration. They measured player’s specific gravity. They even tested urine. Colleges and many high schools began following the NFL’s lead. After some lawsuits and acrimony, the NFL made peace with Stringer’s family and lent its muscle to the founding of the Korey Stringer Institute.

The tone of training camp reports changed, too. After a summer when every beat writer in the nation grilled the local coaches on what they were doing to prevent heat stroke deaths, there was a lot less talk about hefty linemen sweating off the flab and a lot more awareness of the need to practice safely and properly.

Dixon is now a high school football coach. Awareness of hydration and heat stroke concerns has reached the point that he does not need memories of his training camp roommate to remind him to provide cool zones and rest breaks.

“There are a lot of courses that we take now,” he said. “We try to identify situations where the temperature, heat index and humidity are dangerous.”

But there is still work to be done. The National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research reported 13 heat stroke deaths during football practices or games from 2010 through 2014.

“Despite an awful lot of effort in that area, and despite people tracking that area closely, we still see it as a major problem,” said Dr. Robert Cantu of the NCCSIR. “A majority of these heat stroke deaths are at the high school level, and that’s where the education isn’t as good as it is higher up the chain.”

Casa said that there are still states where high school football season begins with three three-hour sessions per day in the midsummer heat. There are still schools without athletic trainers and coaches without an understanding of the risks. Meanwhile, in the 14 states that meet Korey Stringer Institute minimum guidelines, there have been zero heat stroke deaths.

“That’s the most staggering piece of data I can tell you,” Casa said. “We basically have saved 20 to 25 lives in those states in the last four years.”

Stringer’s death saved lives not just by forcing changes, but by changing opinions. Awareness of the dangers of heat stroke paved the way for awareness of the dangers of concussions among NFL players—who began prioritizing safer, shorter, less frequent practice sessions in collective bargaining negotiations—coaches at all levels and the public at large.

You can still hear outdated tough-guy attitudes about playing through heat exhaustion (or a seemingly minor head injury) shouted from the backs of sports bars or the bottoms of comment threads, but you don’t hear them during telecasts or meet-the-coach nights often anymore. Stringer’s death forced many of us to be smarter about the risks football players take for our entertainment.

“The whole NFL community was rocked by it,” Birk said. “You know football’s dangerous, but to play it you have to fool yourself into thinking, ‘That’s not going to happen to me. It’s not going to happen to anybody.’ Then, when something does happen, it’s like you realize that you kind of forgot that this can happen. It shakes you. It shakes everything about you. When you go on the field, you think about it. You think, ‘What if that was me? What about my wife?’

“I don’t want to say it’s a good wake-up call. It’s a shitty wake-up call.”

Mike Tanier covers the NFL for Bleacher Report.

Source: Bleacher Report