By Michael Ollove

Another high school football player, this one a 14-year-old in the Bronx, collapsed on the field and died last week, possibly the result of high heat and humidity.

The death of Dominick Bess of apparent cardiac arrest came at a time when thousands of high school athletes have returned to practice fields. It again raises the question of whether states are doing enough to ensure that student-athletes are safe as they collide into one another, run wind sprints, or dig in against hard-throwing pitchers.

Nearly 8 million kids participated in high school sports last year, the most in U.S. history. The shocking deaths of young student-athletes have prompted some states to weigh major changes.

The California Legislature is considering a bill that would bring athletic trainers under state regulation. Others, including Texas and Florida, are strengthening policies on training during high heat and humidity and on the use of defibrillators during sporting events and practices. They are also moving to require schools to devise emergency plans for managing catastrophic sports injuries. And in response to growing concerns about concussions, the state of Texas recently embarked on the largest study ever of brain injuries to young athletes.

But overall, a just released study of state laws and policies on secondary school sports found that all states could do more to keep high school athletes safe. And some have a long way to go.

The study has prompted a strong pushback, including from the national organization that represents state high school athletic associations. But it also has encouraged some athletic trainers and sports medicine physicians who hope poor rankings will impel their states to make improvements and avoid exposing student-athletes to needless risk.

“I was embarrassed we were last,” said Chris Mathewson, head athletic trainer at Ponderosa High School in Parker, Colorado, speaking of his state’s showing in the study’s ranking of state safety efforts. “My hope is it will kick people in the pants and get people to do something about it.”

The rankings were devised by the Korey Stringer Institute (KSI), also known as Stringer, which is a part of the University of Connecticut and provides research, education and advocacy on safety measures for athletes, soldiers and laborers engaging in strenuous physical activity. It was named for a Minnesota Vikings offensive lineman who died of heat stroke during a preseason practice in 2001. His death sparked changes in NFL training practices and influenced reforms at the college and high school levels as well.

The rankings are based on whether states have adopted more than three dozen policies or laws derived from recommendations published in 2013 by a task force that included representatives from KSI, the National Athletic Trainers’ Association and the American College of Sports Medicine. The recommendations cover such areas as prevention of heat stroke, cardiac arrest and head trauma, as well as qualifications of school athletic trainers and educating coaches in safe practices.

Some state athletic associations, including Colorado’s, and the National Federation of State High School Associations, known as NFHS, which represents the associations that govern high school extra-curricular activities, have objected to the methodology of those rankings. They say it relies too much on information found on the websites of state athletic associations while failing to note efforts those groups have undertaken to reduce risks to high school athletes.

“By ‘grading,’ state high school associations based on a limited number of criteria, KSI has chosen to shine a light on certain areas, but it has left others in the dark,” said Bob Gardner, NFHS executive director. He pointed to steps his group and its members have taken related to safe exertion in heat and humidity, use of defibrillators and tracking head injuries, which Stringer didn’t take into account.

In Colorado, Rhonda Blanford-Green, commissioner of the state’s High School Activities Association, said officials are “comfortable and confident that our [policies] meet or exceed standards for student safety.”

She complained that Stringer’s methodology is too rigid. For example, she noted that Stringer penalized states that did not require that all football coaches receive safety training taught by USA Football, the governing body for amateur football. But, she said, Colorado coaches are trained in other programs that she described as more comprehensive.

She also noted that her association was penalized because it made policy recommendations to its high school members, rather than making them requirements, as Stringer prefers.

The scholastic association in California, which finished just ahead of Colorado, also objected to the survey. Its executive director, Roger Blake, suggested that funding was a chief barrier to progress.

California Interscholastic Federation “member schools will need more funding, more AEDs [automated external defibrillators], more athletic trainers and more research to help support our efforts to minimizing risk,” Blake said. “With the assistance of everyone who cares about young athletes, including KSI, we can continue to progress.”

High School Deaths

Between 1982 and 2015, 735 high school students died as a result of their participation in school sports, according to the National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research at the University of North Carolina. The vast majority of those deaths were related to football, and three-quarters of the overall deaths were attributed to cardiac arrest, respiratory failure or other ailments associated with physical exertion. The rest were linked to trauma, such as head injuries.

More of those deaths occurred in the 15 years prior to the year 2000 rather than the 15 years after — likely a reflection of the fact that most of the policies and laws pertaining to safety in high school sports were put in place after 2000, particularly in the last nine years.

In 2014-15, the last year for which there are statistics, 22 high school athletes died, 14 of them football players.

Some of the reforms carry the names of student-athletes who died while participating in school sports. That was true in North Carolina after the 2008 death of Matthew Gfeller, a 15-year-old sophomore linebacker who died in the fourth quarter of his first varsity game in Winston-Salem after colliding helmet-to-helmet with another player.

Now a foundation and a brain injury research institute at the University of North Carolina are named after Matthew. His name and that of another North Carolina high school football player, Jaquan Waller, who died the same year as a result of on-field head injuries, are attached to a 2011 North Carolina law that specifies concussion education for coaches and concussion protocols to be followed in high school athletics.

“Was the information out there in ’08?” said Matthew’s father Robert, who created the foundation. “No, but it’s out there now, big time.”

Despite the progress, the Stringer rankings demonstrate the distance many athletic trainers and doctors believe states still need to go to protect student-athletes.

For instance, although North Carolina finished No. 1 in the Stringer rankings, it has adopted only 79 percent of the laws or policies used in the rankings. In particular, Stringer found the state hadn’t done enough to make certain that defibrillators — and people trained to use them — were present at sporting events.

A Sense of Urgency

Many athletic trainers, such as Jason Bennett, president of the California Athletic Trainers’ Association, say the rankings should create urgency in his state and others. “This is life and death,” Bennett said. “The sad thing is that in many of these cases, the deaths were 100 percent preventable.”

California fared particularly poorly because it is the only state that does not regulate athletic trainers.

“Sometimes it’s the school’s janitor or maybe a friend of the coach,” said Democratic California Assembly member Matt Dababneh, who introduced a bill that would create state licensure for athletic trainers. “These are people who are making decisions about whether a kid who has just been hit in the head can safely go back into a game. And they have no qualifications to make that decision.”

The bill would not require all schools to employ an athletic trainer, although that’s exactly what many athletic trainers and sports medicine doctors say would best ensure the safety of student-athletes.

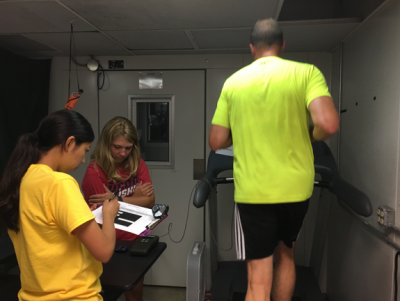

“The No. 1 thing we can do to make high school and youth sports safer is to have athletic trainers at any sporting event,” said Michael Seth Smith, co-medical director of a sports medicine program at the University of Florida focused on sports medicine for adolescents and high school students.

A survey from Stringer and others published this year found that fewer than 40 percent of public secondary schools in the U.S. had a full-time athletic trainer.

Mathewson, the athletic trainer in Colorado, said he has little sympathy for smaller schools who say they can’t afford athletic trainers. “If you can afford to put a football team on the field, you should be able to afford an athletic trainer.”

In a number of places, including in Florida and North Carolina, hospitals subsidize athletic trainers working in public schools, some in the expectation that after a year or two, the school district will pick up the costs.

Aside from the salary of an athletic trainer, schools could adopt most of the best practices at an initial cost of $5,000 and an outlay of less than $2,500 a year thereafter, according to Stringer CEO Doug Casa.

Source: The Pew Charitable Trusts