(Reuters Health) – A thousand-dollar expenditure for an automated external defibrillator (AED) could mean the difference between life and death for some young athletes, a cost that one Little Rock, Arkansas high school knows too well.

A heart abnormality caused 16-year-old Antony Hobbs to collapse during his Parkview High basketball game in 2008. Hobbs was unaware of his condition, likely present since birth. Though an ambulance responded, he died about an hour after an otherwise ordinary game tip-off.

The outcome differed starkly two years later when another Parkview player, Chris Winston, collapsed on court with the same condition. A new state law, named for Hobbs, had required that AEDs be placed in schools, and AED use led to Winston’s survival.

While Arkansas’ policy followed tragedy, the National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA) and the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine are asking schools to proactively take measures to protect kids before summer training for fall sports.

“We’ve mostly been reactionary in terms of our preparations,” said Jonathan Drezner, a University of Washington sports medicine physician and co-author of an editorial in the Journal of Athletic Training that calls for emergency practice implementation in schools. “It shouldn’t be that a kid has to die for the school to be prepared,” he said.

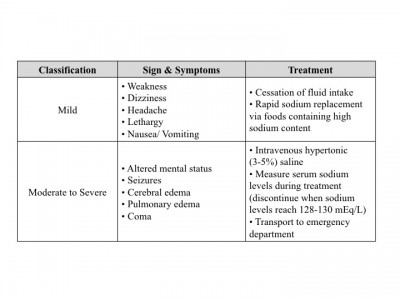

In 2014, 11 high school football players died during practice or competition, according to the National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research. Five deaths were a result of brain injury or cervical fracture. Six were the result of heart conditions, heat stroke or water intoxication.

“AEDs are a relatively inexpensive way of saving a life,” said Doug Casa, CEO of the University of Connecticut’s Korey Stringer Institute, which works to prevent sudden deaths in sports. Casa authored NATA’s “best practice” guidelines in 2012 for school sporting events (available online here: bit.ly/1g5QXdr).

In addition to calling for AEDs onsite, the guidelines advise schools to develop heat acclimatization programs, with phase-ins of equipment, along with gradual increases in intensity and duration of exercise. Football practice in early August is the most dangerous time for heat strokes in young athletes, according to the organization.

The recommendations also call for schools to coordinate their emergency plans with local emergency services.

Nationwide adoption of the guidelines has proven slow, however. Only 14 of 50 states, for example, meet NATA “best-practices” regarding heat.

And according to the Sudden Cardiac Arrest Foundation, only 19 states have laws mandating AEDs in at least some schools.

Jason Cates, an athletic trainer for Cabot Public Schools in Cabot, Arkansas, was among those who worked for changes after Hobbs’ death to ensure the safety of Arkansas’ student-athletes. For districts with limited budgets, he suggests enlisting support from local booster clubs and parent-teacher organizations, and holding fundraisers during games.

To schools that install new turf or expensive video screens instead of safety measures, Cates says, “If you can afford to do that stuff, you can afford athletic health care.”

Source: Reuters