New Jersey Leads National Effort to Adopt

Lifesaving Measures for High School Athletes

“Raise Your Rank” campaign encourages all states to adopt important safety guidelines

NEW JERSEY– Many states across the country are not fully implementing important safety guidelines intended to protect student athletes from potentially life-threatening conditions. Research has shown that nearly 90 percent of all sudden death in sports is caused by four conditions: sudden cardiac arrest, traumatic head injury, exertional heat stroke, and exertional sickling. Adopting evidence-based safety measures significantly reduces these risks. With more than 7.8 million high school students participating in sanctioned sports each year, it is vital that individual states begin taking proper steps to ensure their high school athletes are protected. The call for action came this past fall when the University of Connecticut’s Korey Stringer Institute (KSI), a national sports safety research and advocacy organization, released a comprehensive state-by-state assessment of high school sports health and safety policies. New Jersey currently ranks 4thnationally in terms of meeting all of the recommended safety guidelines with a score of 67%.

KEY INITIATIVES:

In response to the findings, New Jersey officials are collaborating with the KSI in addressing existing gaps in state policy to improve high school athlete safety. New Jersey is the first state to join the KSI’s national “Raise Your Rank” campaign, which started in 2018. The campaign aims to raise funds to support meetings with state representatives in order to improve mandated best practice policies and increase implementation of those policies.

“With support and guidance from the experts at the Korey Stringer Institute, the New Jersey State Interscholastic Athletic Association and Senator Patrick Diegnan (D-Middlesex) will convene this week to begin taking the necessary steps to improve the health and safety of our secondary school athletes,” says David Csillan (Ewing HS Athletic Trainer and NJSIAA Sports Medicine Advisory Committee). “Our goal is to be the first state to be 100% compliant with the recommended safety guidelines.”

This is not the first time New Jersey has led the way in improving the health and safety of high school athletes. New Jersey was the first state to implement heat acclimatization policies for high school athletes in 2011. Acclimatization policies require teams to allow athletes to adjust to hot conditions in late summer by phasing in practices, participating without heavy equipment, and requiring frequent breaks to allow athletes to recover and stay hydrated. Since 2011, six states have implemented similar heat acclimatization policies with positive results; there have been no reports of exertional heat stroke deaths in states where acclimatization policies are in place and properly followed.

“A hallmark of my tenure of as a legislator, working collaboratively with the Athletic Trainers’ Society of New Jersey, is to make New Jersey high school sports safer for our children by creating researched-based state policies to address preventable sudden deaths,” says Sen. Diegnan. “My hope is that through this conscientiousness partnership, we will shine a light on the great measures this state legislature has taken to restrict cardiac arrest, exertional heat stroke, and head injury deaths in our student athletes and to develop further needed changes to ensure all athletes enjoy their high school sports experiences — and live to tell about them.”

KSI CEO Douglas Casa has been leading KSI since its inception in 2010 and has made athlete safety a focused effort of the institute. “We know that implementation of these important health and safety policies has dramatically reduced sport-related fatalities,” says Casa. “We are excited that New Jersey is taking action to continue to improve its policies and become a leader in minimizing sport-related high school deaths.”

For more information about the Raise Your Rank campaign, including how to apply for KSI support and how to donate to the cause, please visit ksi.uconn.edu.

Media Contacts

Douglas Casa, Korey Stringer Institute, UConn David Csillan, NJ Sports Medicine Advisory Committee

Douglas.casa@uconn.edu njatc5@gmail.com

(860) 486-0265 (office) (609) 651-3053 (cell)

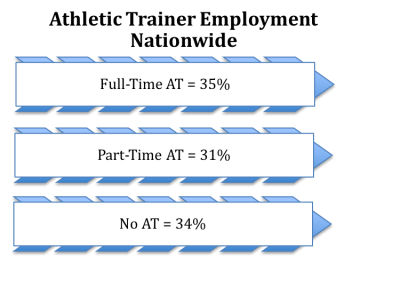

, working either full or part time and providing care for the student-athletes during treatments and rehabilitation programs, practices and game competition.

, working either full or part time and providing care for the student-athletes during treatments and rehabilitation programs, practices and game competition.